ARTS AND CULTURE INFORMATION GATEWAY

Immerse yourself in the colorful world of art and culture! From traditional heritage to contemporary works, discover uniqueness that reflects the nation's identity and identity

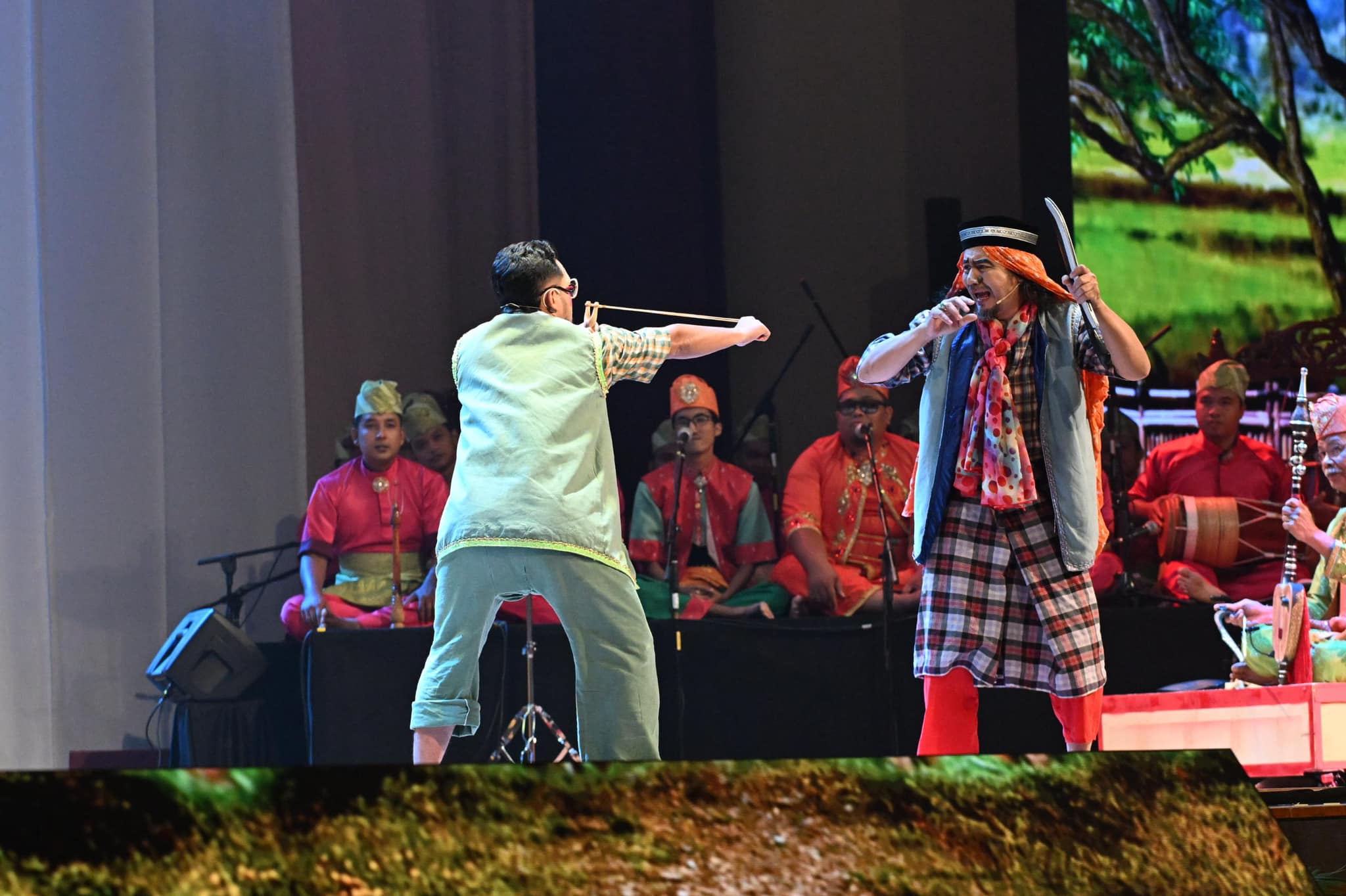

MAKYONG (KELANTAN)

Picture

25

Video

Available

Today's Visitor

4

Number of Visitors

3731

Introduction and history

Makyong is one of the traditional Malay performing arts that is highly unique and refined in nature. It integrates elements of dance, music, drama, singing, ritual, and comedy into a circular theatrical form that is both dramatic and narrative. Originally, its performers were composed entirely of young and beautiful women who played both male and female roles, except for the comedic characters known as peran. The exclusive selection of female performers was closely tied to its function as entertainment within the royal courts, specifically for queens, princesses, and female nobility. This practice arose out of concern that the presence of male performers, particularly during the absence of kings or noblemen attending to state matters, might lead to romantic entanglements.

The origins of Makyong can be traced back at least 200 years, based on records in the Hikayat Patani, which state that it first developed at the Yala palace of the Pattani Kingdom before spreading to Kelantan. From there, it expanded to Kedah, Singapore, the Riau Archipelago, and the Johor-Riau-Lingga Sultanate. Initially, Makyong was performed exclusively at royal courts, particularly among the aristocracy. Documentation of Makyong performances can also be found in Syair Perkawinan Anak Kapitan Cina written by Encik Abdullah in 1277 Hijrah (1860 AD), which describes the wedding of Engku Puteri Raja Hamidah and the son of a Chinese Kapitan.

However, with the arrival of the British in Kelantan in the early 20th century, the economic and political power of the royal elite declined, which led to Makyong spreading to the villages, no longer under royal patronage. This development resulted in changes to the form of Makyong performances during its second generation (following the great Bah Air Merah flood of 1926 until the 1950s).

In 2005, UNESCO recognized Makyong as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, an acknowledgment that elevated the importance of this art form in the context of global cultural heritage. This recognition further reinforced Makyong's significance in preserving Malay cultural identity and heritage. Today, various parties are actively involved in documentation, training of successors, and preservation efforts to ensure that the original form of Makyong continues to be passed down to future generations.

In its earliest existence, Makyong was deeply rooted in the traditional healing rituals of the Malay community, particularly in Kelantan and its surrounding regions. The performance played a crucial role in spiritual healing ceremonies, believed to cure illnesses thought to stem from internal imbalance or spiritual disturbances. In this context, Makyong was not merely a form of entertainment but served as a medium connecting patients, healers, and the spiritual realm. Through a combination of singing, rebab music, dance movements, symbolic dialogue, and ritual incantations, a therapeutic atmosphere was created to facilitate the patient’s spiritual recovery.

Over time, as social and political dynamics evolved, the function of Makyong also experienced a shift. From its origins as a healing ritual, it developed into a form of exclusive court entertainment, particularly within royal families and the nobility. Makyong performances in royal courts were often held to celebrate important occasions such as royal weddings, birthdays, and various palace festivities. Within this royal setting, Makyong was not only seen as entertainment but also as a symbol of luxury and cultural refinement that reflected the elevated social status of the rulers.

As royal authority began to decline, particularly with the arrival of British colonial rule in the early 20th century, Makyong continued to flourish among the general public in village communities. It gradually became part of the people’s entertainment, performed during weddings and local customary celebrations. Although performances outside the palace were no longer bound by aristocratic protocols, they still retained their dramatic elements, comedy, traditional music, and narratives rich with moral values, advice, and social satire.

Costumes and accessories play a crucial role in enhancing the aesthetic beauty and defining the identity of characters in Makyong performances. In addition to strengthening the dramatic elements, costumes also reflect the social status, roles, and historical backdrop depicted in the performance. The costumes worn by Makyong performers are typically made of luxurious fabrics such as songket, satin, silk, or brocade, richly decorated with gold and silver thread embroidery. The design of Makyong costumes is deeply influenced by traditional Malay textile arts, woven with symbolic meanings unique to the culture.

Music plays a very important role in Makyong performances. It not only serves as accompaniment for singing and dancing, but also creates a dramatic atmosphere, controls the rhythm of the performance, and signals both the audience and the actors about scene transitions or the appearance of characters. The main musical instruments used in Makyong are as follows:

Rebab

The rebab is the principal musical instrument in Makyong performances. Structurally, the rebab consists of three main parts: the "pucuk rebung" (tip), the body, and the face. The face of the rebab is made from jackfruit or sena wood, covered with cowhide. A small hole on the face is sealed with a cover known as the susu or tetek, which functions to balance the air pressure inside and outside the chamber. The chamber itself is made from jackfruit or sira wood. In the past, the rebab strings were made from thick thread, but have since been replaced with guitar, oud, or violin strings, as used today. The bow of the rebab is made from wood and synthetic strings.

The structure of Makyong performances is highly systematic and typically follows a fixed sequence of songs and dialogues. The performance begins with Bertabuh, followed by Mengadap Rebab, then a dialogue between the King or Pak Yong and Makyong. This is followed by Pak Yong Muda or Puteri Makyong singing Dondang Lanjut, along with a series of subsequent dialogues and songs such as Sedayong Pak Yong, Kisah Barat by Pak Yong Muda, Barat Cepat by Peran, Lagu Berkbabar, Lagu Saudara, a repeat of Barat Cepat, Tok Wak, and Lagu Ela, which lead into the main storyline.

Each Makyong performance usually begins with the Mengadap Rebab ritual, which serves as a mandatory opening for every show. During this segment, the main character delivers a solo song accompanied by the rebab, while the chorus, known as Jong Dondang, repeats the verses sung by the lead character. Throughout the Makyong performance, the role of the rebab player, known as Tok Minduk, is crucial. Tok Minduk serves as the leader of the musical ensemble and is responsible for initiating every song by playing an introductory melody for 8 to 16 measures before the other instruments join in. In addition, Tok Minduk signals the beginning of songs, arranges tempo changes, and controls the musical aspects throughout the performance. All Makyong songs are fully memorized by Tok Minduk, who also performs the buka panggung (stage opening) ritual. During the performance, musicians are positioned at the left corner of the stage, while Tok Minduk sits facing the setting sun.

During the singing, actors perform refined hand, shoulder, and body movements slowly and gracefully. Upon completion of the solo song, all performers rise slowly and stand upright before beginning to circle the stage with slow dance movements, while one performer continues with the next solo known as Sedayong Makyong.

Dance also plays a significant role in accompanying the songs and dialogues. Makyong dance emphasizes gentle and symbolic hand movements, coordinated with the movements of the head, body, and feet. Basic movements used include Duduk atas tumit dengan Sembah Guru, Susun Sirih, Gajah Lambung Belalai, Burung Terbang, Ular Sawa Mengorak Lingkaran, Seludang Menolak Mayang, Sulur Memain Angin, Liuk Kiri Longlai Ke Kanan, Berdiri Tapak Tiga Menghadap Timur, Sirih Layer, Kirat Penghabisan, Langkah Turun dan Naik Kayangan, as well as Pergerakan Berjalan Pak Yong.

Characters and Characterization

Ruhani binti Mohd Zin. (2009). Persatuan Warisan Sary, No.44, Jalan Padang Tembak Perumahan Padang Tembak, 16100 Pengkalan Chepa, Kelantan.

Reference Source

Bahan Bacaan Yousof, G. S. (1976). The Kelantan" Makyong" Dance Theatre: A Study of Performance Structure. University of Hawai'i at Manoa. Yousof, G. S. (2017). The Makyong dance theatre as spiritual heritage: some insights. SPAFA Journal, 1. Hardwick, P. A. (2020). Makyong, a UNESCO “masterpiece”: Negotiating the intangibles of cultural heritage and politicized Islam. Asian ethnology, 79(1), 67-90. The revitalization of Makyong in the Malay world Hardwick, P. A. (2009). Stories of the wind: The role of Makyong in Shamanistic healing in Kelantan, Malaysia

Location

State JKKN Contact Information

Encik Wan Mohd Rosli bin Wan Sidik

Cultural Officer

Jabatan Kebudayaan dan Kesenian Negara, Kelantan

Kompleks JKKN Kelantan

Lot 1993, Seksyen 49,Tanjong Chat,

15200, Kota Bharu,

KELANTAN DARUL NAIM

09-741 7000

Persatuan Warisan Sary, No.44, Jalan Padang Tembak Perumahan Padang Tembak, 16100 Pengkalan Chepa, Kelantan

Persatuan Warisan Sary, No.44, Jalan Padang Tembak Perumahan Padang Tembak, 16100 Pengkalan Chepa, Kelantan